Suburban Bohemia: The Northernmost Point of the Czech Republic

Adventure is calling.

By chance, I’ve stumbled across a Wikipedia entry listing the extreme points of the Czech Republic — the northernmost, westernmost, southernmost and easternmost municipalities in the country — and an idea takes hold.

Why not revive my Suburban Bohemia blog then write up my findings?

I can think of a few reasons, to be honest — time, expense, inconvenience — but nothing that can’t safely be ignored.

Most significantly, history and economics mean Czech border towns are rarely conventionally attractive places to visit. Three of the four extremities are in the former Sudetenland — areas that the German-speaking majorities were forcibly evicted from at the end of World War II. The fourth is closer to Ukraine than to Prague.

Another snag, as far as adventuring goes, is that I now have a young daughter, and a wife who isn’t particularly interested in visiting sketchy border towns. Being realistic, I figure I can visit and write up one extremity per year without neglecting other duties.

Being a northerner, I decide to start in the north, in Severní (literally “Northern”), a clump of country cottages just north of the village of Lobendava.

The northernmost area of the Czech Republic is known as the “Šluknov Hook” (Šluknovský výběžek), which sounds like something that would get you 10 minutes in the box but is actually the name of the northern Bohemian peninsula (technically a salient) that curls up into Saxony.

The northernmost settlement on Czech territory used to be Fukov, about six kilometres north-east of the town of Šluknov. The amusingly named village’s population dwindled in the aftermath of World War II, however, and when Fukov’s last few residents moved on in 1960, the title of northernmost Czech settlement moved around 15 kilometres west, to Severní.

Friday 29 March, 2019: Severní and Beyond

The Czech Republic has extensive bus and train networks, but there’s a catch. It’s easy to get out of Prague but, unless you head back home in the early afternoon, it’s often pretty difficult to get back to the capital. And at weekends, the options are even more limited.

To make my trip possible via public transport (which means I can enjoy a couple of beers along the way) I’ve taken a Friday off work and will stay overnight in a hotel in Varnsdorf.

So, at 9:45am I catch a bus from outside Prague’s Nádraží Holešovice railway station to Rumburk — a journey of contrasts that combines the natural beauty of Kokořínsko with the less obvious delights of industrial and post-industrial northern Bohemia.

In Nový Bor, they’re advertising flats for 3,000 crowns a month — a sixth of the price we pay in Prague — but, apart from local glassmaker Crystalex’s space-age headquarters, the town doesn’t look very inspiring.

I don’t see much of Rumburk in the time it takes to change buses, and wish I’d seen more.

As we get closer to the border, I spot the occasional German-language ghost sign, and wonder why nobody bothered to remove them in the intervening 74 years.

Time is tight so I set off walking to Severní as soon as the bus drops me in Lobendava, a pretty country village.

Lobendava is quiet on a Friday afternoon, and the countryside north of Lobendava even quieter. It feels like I have the northernmost chunk of the Czech Republic to myself.

I’m only a few hundred metres out of Lobendava when I pass the entrance to a brothel (“Privat Club Kittelberg”), which kills the idyllic country vibe a little, but the rest of the walk to Severní is pleasant enough.

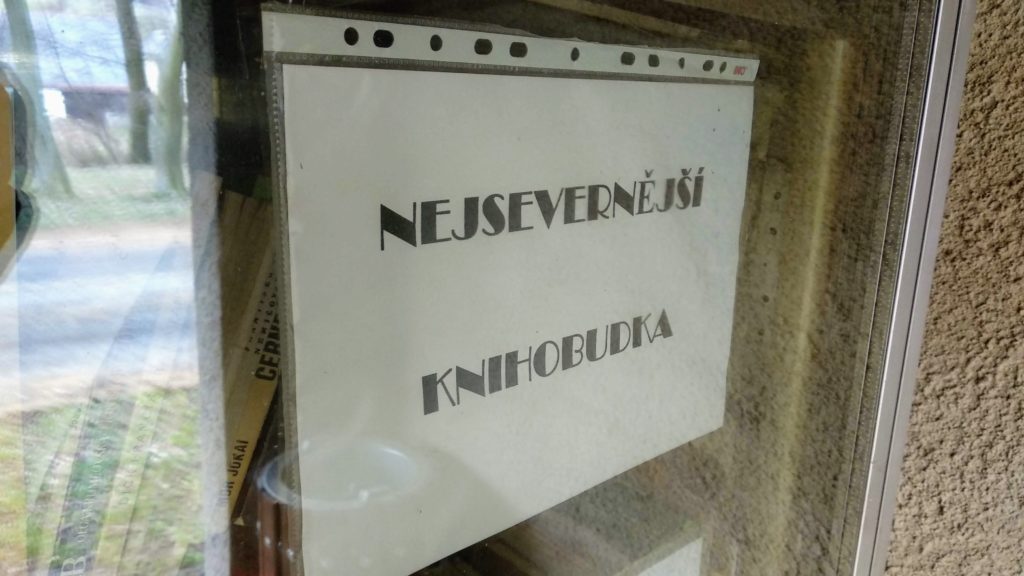

Severní itself, with a population of around 60, doesn’t have a lot to offer thrillseekers but there is a knihobudka (public bookcase) at the bus shelter, inevitably billed as the “northernmost public bookcase”.

Upside-down cups have been placed over the fence posts of the house opposite — a charming Slavic tradition originally intended as an invitation to travellers to help themselves to water but now mainly used for decoration.

I take a few snaps and trudge on to the border, which, to commemorate last year’s 100th anniversary of the founding of Czechoslovakia, has been marked with a jauntily painted historic border post.

I have lunch — a flask of soup — in Germany, just because I still can, then follow the walking trail into the woods in search of the northernmost point of the Czech Republic.

I’m encouraged to have read that, since 2013, a two-tonne commemorative stone has marked the northernmost point, which gives me something to aim for.

It’s not long since strong winds battered this part of the Czech Republic, so there are a lot of trees down. Without too much trouble, though, I find my way to the northernmost stone and take the obligatory selfie, smiling my best Gordon Brown smile.

Rather than go back the way I came, I decide to take a more scenic route, following the yellow tourist path westward along the border before looping back round to Severní.

This is a mistake.

Because of all the fallen trees, it becomes impossible to stick to the yellow path and I get lost.

I fear I’m going to end up in one of those news stories about hopelessly unprepared city folk heading into the wild: I have no map, no water and only a tiny packet of Haribo gummies that’s been lurking in my backpack for almost a year, in case my daughter gets hungry on day trips.

This isn’t the way I want to die, lost and alone in a forest, listening to a Prince song about dolphins.

More to the point, my phone is low on battery and all the information I need to check into the hotel in Varnsdorf is on there.

I switch mobile internet off to save battery and rely on my phone’s location services, which are accurate enough to help me find an alternative path.

By now, I’m way off course, though, and heading into Germany.

I emerge from the wilderness by a sinister-looking medical facility, the Asklepios Orthopädische Klinik Hohwald. (Who builds a private hospital in the middle of the woods, right next to the Czech border? And why?)

A little further on, I enter Hohwald itself. It isn’t much more than a collection of houses but I’m relieved to be back among humanity. I’m pretty sure I won’t be eaten by bears now.

It’s nearly six kilometres from Hohwald back to Lobendava but the path is easy to follow.

I eat the gummies, my phone battery finally dies, and I arrive in Lobendava just in time to miss the 16:33 bus to Varnsdorf.

It’s two hours until the next bus so I head to the village’s only pub, U Hraničář (“At the Border Guard”), for fried cheese and beer.

Surprisingly, they serve Bernard, a beer I associate with middle-class Praguers and students. It’s a beer I don’t normally drink, because the owner’s a bit of a dick, but after a long walk in the woods it goes down pretty easily.

Eventually, the bus arrives. My fellow passengers mainly seem to be teenage kids heading into Rumburk for Friday night action.

It’s dark when I get to Varnsdorf and, with no Google Maps to guide me, I take a taxi to my accommodation, driven by a friendly young man who speaks English.

The snappily named Vzdělávací Středisko a Hotel (“Educational Centre and Hotel”) appears to be locked for the night when I get there but there’s a phone number on the door.

Hoping to charge my phone, I go to the bar across the street. It’s an odd place — there’s still a Christmas tree up, even though it’s late March — but when I explain my problem to the barmaid, she instantly offers me her phone to make the call.

I tell her that isn’t necessary and plug my charger in at a nearby table.

I’d expected the hotel receptionist to be annoyed that I’d interrupted her Friday night but she’s very understanding.

When I get to the hotel, she shows me the kitchenette where my breakfast is already prepared for tomorrow morning, then tells me to drop the key in the box when I leave. I get the feeling I’m the only guest in the hotel.

I fall asleep watching Brexit coverage on ČT24, the Czech news channel.

Saturday 30 March, 2019: Varnsdorf

I check out on Saturday morning and, after picking up a map of local walking trails from the tourist office, try to get a feel for Varnsdorf before the bus leaves for Prague.

Varnsdorf doesn’t have the best reputation these days.

In the 19th century, a successful textile industry earned the town a place among the many Central European towns with a Manchester-themed nickname. (In this case, the “North Bohemian Manchester” (“Severočeský Manchester”) — an honour shared with Liberec — and, according to Wikipedia, the somewhat confusing “Little Manchester in the Czech Netherlands”.)

Before 1945, the town was named Warnsdorf and, its 20,000+ population was at least 90% German. Following the post-war expulsions, the population of the town — now Varnsdorf with a V — shrank by around a third, despite a government campaign to encourage Czechs to claim German-owned property in the border regions.

In a particularly shameful episode, workers in Varnsdorf staged a strike in 1947 to prevent Emil Beer, a German-Jewish factory-owner who’d fled the Nazis in 1938, from reclaiming his old property.

The results of the expulsion and resettlement are still being felt today, according to economists.

In The Economic Legacy of Expulsion: Lessons from Postwar Czechoslovakia, University of California, Irvine’s Patrick Testa finds that, as of 2011, towns that were resettled still had higher unemployment, lower levels of educational attainment, and smaller skill-intensive economic sectors than equivalent Czech towns.

And in Old Sins Cast Long Shadows: The Long-Term Impact of the Resettlement of the Sudetenland on Residential Migration, another 2019 paper, Martin Guzi, Peter Huber & Štěpán Mikula found evidence to suggest that residents of the former Sudetenland feel less of a connection to their hometown than other Czechs. (As well as having slightly higher emigration and immigration rates, residents of resettled Sudetenland communities are less likely to vote in local elections, join local clubs or organize social events.)

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that there seems to be a correlation between the areas formerly inhabited by German-speakers and the areas that voted for Miloš Zeman, an anti-immigration populist, in the 2018 presidential election:

More recently, Varnsdorf was the scene of anti-Romany race riots in 2011, and was back in the news in March of this year (2019) when someone blew up two of the town’s unpopular new speed cameras.

“Varnsdorf is nicknamed ‘The Wild North’,” noted a TV Nova news report at the time of the explosions. “People here react very emotionally.”

I’m hoping to avoid emotion on my visit.

Originally, I’d been planning on visiting the fairytale Hrádek-Burgsberg lookout tower first, then visiting Pivovar Kocour, one of the Czech Republic’s first and best craft breweries, for lunch.

The tower doesn’t open until noon, though, so I end up having a rather hefty brunch of schnitzel and beer at Kocour then sweating my way up the tower steps.

Varnsdorf, on the surface at least, is more affluent than I’d expected.

The area directly below Hrádek-Burgsberg, full of big detached houses, seems comfortably middle class, and, judging by the number of job ads I see dotted around town, unemployment isn’t as much of an issue as it once was.

On my way to the bus station, I stop at Zdravá Kavárna Emavík, a fancy, baby-friendly cafe that wouldn’t feel out of place in Karlín or Vinohrady or some other trendy district of Prague.

The only unpleasant experience I have is when a man shouts at me from his car while I’m photographing local houses. I figure this must be (a) because he thinks I’m casing the joint or (b) because I was standing in the road at the time. Either way, it’s understandable, I suppose.

Otherwise, people are surprisingly friendly.

I assume I’ve just been lucky but, at the bus station, I get talking to an old bloke from Česká Lípa, who, unprompted, mentions how open and friendly people are here compared to his hometown. And a couple of weeks later, I hear the presenters of the Zbrojovkast podcast say more or less the same thing.

The Wild North has been unexpectedly civilised.

Sam Beckwith

Once and Future King of the Internet